`

|

NoesisThe Journal of the Mega Society Issue #186 March 2008 |

About the Mega Society

The Mega Society was founded by Dr. Ronald K. Hoeflin in 1982. The 606 Society (6 in 106), founded by Christopher Harding, was incorporated into the new society and those with IQ scores on the Langdon Adult Intelligence Test (LAIT) of 173 or more were also invited to join. (The LAIT qualifying score was subsequently raised to 175; official scoring of the LAIT terminated at the end of 1993, after the test was compromised). A number of different tests were accepted by 606 and during the first few years of Mega’s existence. Later, the LAIT and Dr. Hoeflin’s Mega Test became the sole official entrance tests, by vote of the membership. Later, Dr. Hoeflin's Titan Test was added. (The Mega was also compromised, so scores after 1994 are currently not accepted; the Mega and Titan cutoff is now 43—but either the LAIT cutoff or the cutoff on Dr. Hoeflin’s tests will need to be changed, as they are not equivalent.)

Mega publishes this irregularly-timed journal. The society also has a (low-traffic) members-only e-mail list. Mega members, please contact the Editor to be added to the list.

For more background on Mega, please refer to Darryl Miyaguchi’s “A Short (and Bloody) History of the High-IQ Societies,”

http://www.eskimo.com/~miyaguch/history.html

and the official Mega Society page,

https://www.megasociety.org/

Noesis, the journal of the Mega Society, #186, March 2008.

Noesis is the journal of the Mega Society, an organization whose members are selected by means of high-range intelligence tests. Jeff Ward, 13155 Wimberly Square #284, San Diego, CA 92128, is Administrator of the Mega Society. Inquiries regarding membership should be directed to him at the address above or:

Opinions expressed in these pages are those of individuals, not of Noesis or the Mega Society.

Copyright © 2008 by the Mega Society. All rights reserved. Copyright for each individual contribution is retained by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Contents

About the Mega Society/Copyright Notice |

|

2 |

Editorial |

Kevin Langdon |

4 |

In Memoriam: Nicholas C. Hlobeczy |

Kevin Langdon |

5 |

Four Poems |

Nicholas C. Hlobeczy |

6 |

Three Photographs |

Nicholas C. Hlobeczy |

8 |

A Day in the Life of a Late-Night |

Rick R. |

10 |

The Tao Can Neither Be Retained nor |

May-Tzu |

11 |

The Cells of Problem 36 |

Chris Cole |

12 |

|

Where

Will the Universe Be When the

|

May-Tzu |

14 |

Life, Death, and the Beyond |

Cedric Stratton |

15 |

|

This space

unintentionally left

|

Kevin Langdon

Due to delays in the publication of Noesis we’re overdue for an election of officers. There are three positions: Administrator, Internet Officer, and Editor of Noesis. Our Constitution permits us to have more than one Editor. If there is more than one candidate we’ll vote “yes” or “no” on each one. I am happy to continue as an Editor but other constraints on my time make it difficult for me to get out more than two or three issues a year and I’d appreciate someone to edit issues alternately with me. Mega members, if you’re interested in running for society office please submit a candidacy statement by the deadline for Noesis #187.

The third incarnation of the Mega Society article in Wikipedia was again nominated for deletion, but the outcome this time was different. The decision after comments and an administrative review was to keep the article.

This issue of Noesis features a memorial to photographer Nicholas C. Hlobeczy and samples of his work, Rick R.’s observations on the life of a late-night talk show writer, Chris Cole’s exploration of the mathematical structure of a problem on the Mega Test, a short piece by May-Tzu, and Cedric Stratton’s thoughts on God and religion.

More Noesis submissions are needed. Please think about writing something or send something from your files for publication. Both Mega-member and nonmember contributions are encouraged.

The deadline for Noesis #187 is April 20, 2008.

Cover: “Hearts Through the Window,” by Nicholas C. Hlobeczy. Copyright © 2008 by Jean Hlobeczy. All rights reserved.

Image on page 5: Copyright © 2005 by Kevin Langdon. All rights reserved.

In Memoriam

Nicholas C. Hlobeczy

1927-2007

Kevin Langdon

Nick Hlobeczy was a great friend of mine, a real searcher, and, like his mentor Minor White, a world-class photographer.

A notice of Nick’s first book, A

Presence Behind the Lens, appeared in Noesis #179 (December 2005).

A new book containing Nick’s writings and photographs is currently in

preparation. Publication will be announced here when the book is released.

A selection of his work can be found at www.hlobeczy.com

and a Google search yields over a thousand hits, a fascinating selection of web

pages about or mentioning his work.

Nicholas Hlobeczy was born in Rankin, Pennsylvania. As some of the stories he tells in his book make clear, he was an extraordinarily sensitive child, foreshadowing his career as an artist and writer. He studied art at the Pittsburgh Institute of Art and the Cleveland Institute of Art and then entered into a long apprenticeship with the noted photographer Minor White. Sensing that Nicholas was a very promising student, Minor assisted him to discover his own way of looking though the lens.

Nick was also a teacher of photography who helped aspiring photographers to discover their own inner vision, both in institutional settings (he taught at Case Western Reserve University and was head of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s photography department) and in his own private workshops.

His subject matter was primarily the natural world; he found in it an opening to a new quality of perception and a means of inner transformation. He always considered this the most important aspect of his own work and his work with photography students. His writing focuses on photography as a craft and a means of inner discovery.

Nick Hlobeczy provided the cover image for Noesis #183, December 2006.

Four Poems

Nicholas C. Hlobeczy

One, Two, Three, One --- March 23, 1984,

revised 1997

From two universes we came

On wings of quickened silver

Out of one to the other

This seed, traversed space.

In this is its seeking

------completion

Here driven so great a greatness

Through a gentle kind loving force

Seeking fertile soil;

Arousing strength

Annealing earth and heart.

Without this what the use our journey?

Then as here a universe spun

Whirling through time

Without time and face,

So, Now

-------created a new space.

The Old Man --- January 1996

The old man dies and begins to be

“That” which is observed.

No longer me though related,

As a freed slave is to a household.

What then is there for me to do

Other than follow God’s commission.

Four Poems. Copyright © 2008 by Jean Hlobeczy. All rights reserved.

A Look Within --- Winter 1984

Over the window sash

Where light winds blow,

In times immortal

Timefulness.

As we view this

Ensnared in knowing

At which place knowing answers live.

We want a timeless light,

That falls alive within

Where questions’ breath is quest.

Winter Stars --- December 15, 1984

Night winter sky black and clear

Stars burning in cold space,

This call to deep sense of life.

Drams of boundless time and timeless face

Bright star specks that shine

All mystery; hearken us

To love’s completion,

Within our own small frame.

Now, in this life

We find constellation

Borrowed for a span; removed for a spell

Then retuned again to eternity.

How full the heart

At night tide on the lane.

Brisk air fills winter space,

And stars in their heavens beacon us.

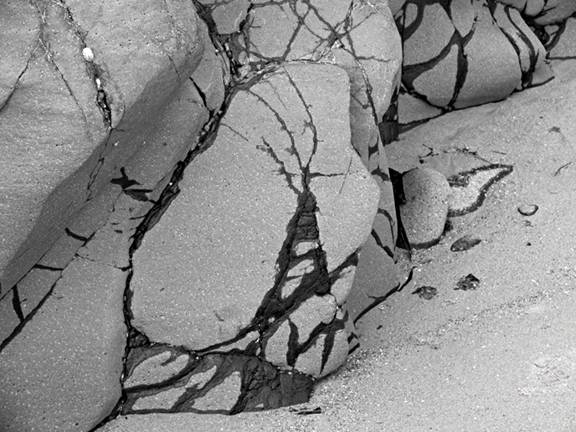

Three Photographs

Nicholas

C. Hlobeczy

The photographs displayed here provide a glimpse of the work of this gifted photographer. For more of his work see his website:

The titles of the photographs on these two pages are “Hearts-Yachats,” “Seeking Stability,” and “Mystic Tree,” respectively.

Three Photographs. Copyright © 2008 by Jean Hlobeczy. All rights reserved.

A Day in the Life of a Late-Night Comedy Writer

Rick

R.

My wife wakes up at 5:35 to get ready to get our daughter ready for school. She wakes me up at a quarter to six. I turn on Headline News and MSNBC, looking for stupid stories my boss can make jokes about in our Act One (his opening monologue). For instance, Jamie Lynn Spears getting pregnant would be one of today’s topics if we weren’t on strike.

I get to work a little after nine, walking up six flights of stairs to my office for exercise. (All the writers are in pretty good shape. In the 1970s, comedy writers did drugs and had indiscriminate sex. Today, writers go to the gym instead.) I go online, looking at tmz.com and perezhilton.com for more stories of celebrity misbehavior. I check Drudge for non-celebrity news. After writing brief summaries of the possible Act One topics I’ve found, I send a bulletin to the other writers and my boss. Each writer comes up with comedy angles on the topics I’ve sent as well as topics they’ve come up with themselves.

At eleven, we have a writers’ meeting with our boss. We go around the table, with each writer pitching about half a dozen angles and topics. Our boss picks about a dozen of our angles, adding a few of his own. Then we have lunch.

Most of the angles we pitch involve production—shooting a bit, altering a video clip, mocking up a fake product or magazine cover, etc. If our bit has been chosen, we write the script then work with producers, directors, video editors, the casting and graphics departments, etc. to make the bit happen. When a bit is finished, its writer and director show it to our boss, who laughs at it and puts it in the show, rejects it, or tells the writer and director how to make it better.

During the early afternoon, if we’re not doing a bit, we work alone or in small groups, writing jokes about the chosen topics. Each afternoon, our boss gets a total of 120 to 180 jokes from all the writers. He chooses a couple dozen of these for the Act One.

During rehearsal, our boss is shown 12 to 20 funny

clips from the last day or two of TV. (We generally can’t show clips from

a scripted show unless one of that night’s guests is from that show, but we can

show clips from the news and from reality shows.) He picks six to ten

clips. In the late afternoon, writers who aren’t busy with bits gather to

watch a cassette of the selected clips. We say quips after each clip which

are typed up by the writers’ assistants and sent to our boss for him to choose

from.

Throughout the afternoon and into the evening, new topics come up. For instance, we get the east coast network feeds, so we can watch reality competitions such as American Idol three hours ahead of the west coast then come up with clips and bits and jokes in time for that evening’s taping of our show.

Some of us stick around to watch the taping and see how our stuff plays, to see if it’s a tough audience, to see if the guests give good interviews, or to listen to that night’s musical guest.

There’s not room in the Act One for all the stuff that’s been chosen. Late-breaking clips and topics squeeze out earlier material. Of the sixty or so topics pitched at a morning meeting, maybe six will make it to broadcast. Of the 270 or so jokes and quips we write each day, perhaps 12 or 15 will be among the two dozen in that night’s monologue. (Our boss writes much of his own material.) Even after the monologue’s been taped, bits can be cut if they didn’t get laughs or if the show runs long.

So about five percent of our jokes and ten percent of our bit ideas make it to air. But the other stuff doesn’t really go to waste. I think of the jokes that make it onto the show as real particles bubbling up from a sea of virtual particles. You can’t just write the good jokes (though sometimes everybody looks at the monitor like they smelled a fart and you delete a joke). You can’t tell whether a joke will be any good until you’ve at least half written it. Then your writing partners tell you it sucks, you say, “Well, help me make it not suck,” and with their help, sometimes it doesn’t suck. Sometimes a crappy joke inspires a good one. Sometimes our boss rejects the cleverest joke because it doesn’t fit the conversational tone of his monologue. Sometimes a joke is squeezed out by a reality show clip of a dwarf falling into a swimming pool. Sometimes the audience doesn’t laugh because they’re 18 years old and only there to see One Republic.

The Tao Can Neither Be Retained nor Abandoned

The Tao can neither be retained nor abandoned.

Open the door to let in a thief.

If a home has no walls,

a cat is sure to return.

—May-Tzu

The Cells of Problem 36

Chris Cole

There is a sense in which it is impossible to receive a perfect score on the Mega Test. This is because the answer to problem 36 is not known. Ron Hoeflin will score a certain answer as correct even though he admits that he does not know if the answer is correct. His reasoning is that many of the top scorers on the test have given this answer and that therefore it is very likely that this answer is correct. However, this is not the usual standard for claiming to know a mathematical truth.

Most philosophers define knowledge as, roughly, justified true belief. In other words, we know something if we believe it, if it is true, and if we are justified in our belief. There are Gedankenexperiments that show that the issue of justification is subtle. Imagine for example that we claim to know that the Mona Lisa is in the Louvre. Suppose that the real Mona Lisa was switched for a copy last week, but the thief was nearly discovered and had to stash the real painting in a locker in the Louvre. Philosophers would argue that even though the Mona Lisa is in the Louvre, we do not really know this because we are not justified in the right way in believing it. It is true for reasons that are not related in the right way to our justification.

One way to characterize this subtlety is to say that the justification must be causally related to the truth. In other words, the truth of the matter must have caused the evidence on which our justification relies. The fact that the thief was forced to leave the Mona Lisa in a locker in the Louvre is mere happenstance, not causally related to our reasons for believing that the Mona Lisa is in the Louvre, which otherwise would have been incorrect. Therefore we do not know that the Mona Lisa is in the Louvre even though it is.

The traditional form of knowledge in mathematics is the proof. We know something if we can prove it from a generally accepted set of axioms. This, of course, leaves open the question of what set of axioms we should use, but luckily there are several suggested sets of axioms that have been shown to be equivalent. This is not trivial, because there also have been some surprises, such as the independence of the Continuum Hypothesis from the remaining axioms of set theory. But there is no known proof of Problem 36. Over the years I have corresponded with many experts in this area of mathematics on this problem. Here is a typical exchange from 2005:

Dear Professor Hart,

An interesting problem is to find the maximum number of cells that can

be formed from three interpenetrating cubes. The last time I looked

into this and talked to a few people about it, about ten years ago, it

was clear that no one knew how to prove this. Has anything changed in

the last ten years? Do you know anyone who would know how to prove this?

-Chris Cole

Chris,

I don't think anyone knows how to solve a problem like this in general. As a starting point, I would try the well-known compound of three cubes, illustrated on the left tower of Escher's "Waterfall" and see how many cells it has, then see if a perturbation of the positions or orientations gives more cells. But I don't see a strategy for proving that a given arrangement is globally maximum. See:

http://www.georgehart.com/virtual-polyhedra/escher.html

George

Thus we do not have a traditional mathematical proof that the Waterfall arrangement yields that globally maximum number of cells. We do not even have an approach to the problem. Nonetheless, Ron Hoeflin’s decision to score a certain answer as correct does not seem entirely nonsensical. Why is that?

One recent trend in mathematics is to accept something as true if it is sufficiently likely to be true. One example of this trend is probabilistic primality testing. We do not have an efficient algorithm for testing whether a given number is prime, but we do have an algorithm that can test for primality to any given confidence level, say, one part in 10500. Since there are only 1080 or so protons in the Universe, one could argue that a confidence level of 10-500 is good enough. After all, we cannot be absolutely certain that a proof does not contain a mistake, or even that the canonical axioms of mathematics are not flawed in some way. So perhaps this confidence level is good enough in the same sense that a cryptographic system is good enough if breaking it will cost more than stealing the answer from the enemy.

Unfortunately even this relaxed standard of mathematical knowledge does not help us on Problem 36, because the problem is so hard that there are no probabilistic results in the area. The problem is simply beyond the current state of the mathematical art.

Nonetheless, there is a sense in which the answer is known, and this harkens back to the importance of causality. When this problem was posed on the Mega Test, a number of people worked independently on the problem. None of these people communicated with one another. They all came from different backgrounds and tried different approaches. As they worked on the problem, the nature of the problem itself caused them to seek out certain configurations. What Ron discovered was that as people submitted answer sheets, there was a general trend that the higher the score, the greater the number for cells found for Problem 36, up to the number that he now accepts as correct. There were exceptions to be sure, but this was the clear pattern.

In using this standard of truth, Ron was following an emerging trend. For example, essentially all electronic security in the world today relies on a similar procedure. Cryptographic systems rely on one-way functions. It is not known if such functions exist, but cryptographic experts believe that they do because so many people have failed to find efficient algorithms to invert them. This belief is strong enough that trillions of dollars are trusted to it daily. So Ron is in good company.

Ron can be viewed as a scientist observing an experiment. The nature of the experimental setup caused a certain behavior of the system. As evidence accumulated, Ron was justified in concluding that the correct answer to Problem 36 was the one that the system itself caused to emerge. This is perhaps an unorthodox definition of mathematical knowledge, but it is not foreign to methods of knowing in other scientific disciplines, nor is it philosophically unsophisticated.

There are many experimental checks and balances. If the experimental result is repeatable, then we can feel secure in concluding that it is very unlikely that nature has conspired to fool us. When two or more labs can replicate the same results, we tend to believe that hidden systematic biases have been eliminated as an explanation. There is always the risk of confirmation bias, so we run double-blind experiments, which is what Ron did by keeping the answer secret. With enough confirmation our “hypothesis” becomes our “knowledge.”

Where will the universe be

when the paradigm shifts?

Where

will the universe be when the paradigm shifts? The universe is some sort of

humongous quantum-foam Wiki, continually edited mostly unconsciously by every

existent sentient being at every level of scale. ‘Paradigms’, models,

conjectures and instinctual ‘guesses’ of entities

from the infrahuman to the (for us) unimaginably god-like actually modify

Nature in attempting to represent Nature and her workings. Our little truths

are a receding horizon.

—May-Tzu

Life, Death, and the Beyond

Cedric Stratton

In WWII England, December 1941, I contracted TB, recovered, and after recovery the doctors recommended a month in a warm sunny location in the southwest of England. I already attended a boys’ boarding school there, a mere seventy miles away.

By June 1942, US forces were already arriving to prepare for the eventual invasion of France. They were fit, strong, and full of life. They befriended youngsters like me, showed me how to fish, to swim, to ride the waves, the buoyancy of water, rock-climbing and so on.

Upon returning to school I found the servicemen borrowing our school fields for their games. I learned baseball, and as a left-hand batter with a tennis court on my power side I knew what a pennant porch was before I ever heard the words.

I asked for a pen-friend, to help me know more about these energetic people, and John Lepore was the one they selected for me. We exchanged letters for fourteen years, without meeting, before our professional lives interfered, correspondence dwindled, and we lost touch.

Fifty years later, I received a telephone message on my machine starting: “you won’t know who I am, because we have not corresponded for fifty years.” And I guessed immediately it was he. I had never seen him, nor heard his voice. He had become a Roman Catholic priest, become disaffected with the church, went through marine boot camp before serving as a chaplain. He then became a teacher, later earned a Ph.D. in counseling, partook of many sports, mostly involving a racquet, with great success.

We met face-to-face eighteen months ago, and liked each other at once. He is the one who invited his friends to write their views on god, and the separate questions that he posed to us. The article was my response.

He collected all responses, abstracted key features from each, and sent copies to every contributor. Our local newspaper came to hear of this, and I was interviewed. The lady Chris Cole e-mailed for permission to use this piece (Dana Felty), was the one who interviewed me—right inside the church during and after choir practice, actually--and she was the one who put the piece out on the internet.

Seeing the piece, some preacher at a mega-buck mega-church picked it up and on his web-site sarcastically asked, ‘wouldn’t it be nice if we could all just forget about God, and just say we are Christians?’ I did not even bother with him. To me the most important thing about Christianity is aspiring to lead the gentle, compassionate life that Jesus led; God is far less important, and making mega-bucks is the least of all.

Copyright © 2004, 2008 by Cedric Stratton. All rights reserved.

1. Do you believe in God/Supreme Being/Uncaused Cause?

No, I do not believe in a supreme being. My rationale is entrenched in chaos theory. By carefully observing and analyzing the random interactions of large numbers of moving things, we can discern within the apparent chaos many ordered zones persisting for finite, measurable, periods. Logical extension implies that an infinite universe, in time, will display every degree of order within that chaos, albeit surrounded by an overwhelming mass of material in disarray.

Given the magnitude of time, space, and circumstance, the geneses of galaxies, stars, planets and life do not require intervention by a superior being. I suspect that people studying the infinite variety afforded by the Mandelbrot set, or similar fractal systems, likely incline towards this, or a similar, point of view. With the infinite, all things are possible hence the space-time infinity is sufficient unto itself. Over geological time spans there are eras where an order exists with a few materials remaining stable for long periods. Again, over cosmic time, the current geological group of substances may have several forms; one stable set of substances changes to other stable substances, while others resist changes. Some of the unchanged persist; some of the new persist. Human lives, on the scale of geologic and cosmic time are not even a blip on the radar of events. 100,000 years of humanoids in an estimated 10,000,000,000 years of existence of the Milky Way galaxy come to a trifling 0.0001%. The presence of ordered zones in a chaotic system imply that pockets of order come and go within the infinity of time and space, and we (humans, the biosphere, the whole planet) happen to be in one at present.

If he exists, does he care about us?

This is moot, given my answer to the first part. If a being exists who ‘made us in his image’ then, regarding the time when dinosaurs were dominant, before humanoids even existed, I ask ‘in whose image were the dinosaurs made?’ Then again, at some time in the future when humans no longer walk the earth (or any other place), and a new prevailing life form replaces the human domain, in whose image would they be made—in the image of the same god, or a different one? If the same god, he has ceased to care about us; if a different god, the original was not immortal, invisible, etc.

Put differently, why should a being with the ability to exist in all places at once, make all things, do all things (according to one popular concept of god), pause along the way to care for each and every individual creature? When earth changes in a way to render human life impossible, and other life forms have their opportunity for a moment in the sun, the view of a caring god implies that the god must therefore have ceased to care for humans, in favor of the latest viable species.

2. Is life as we know it, the BE-ALL-END-ALL?

I have no problem with saying ‘yes’ to that one.

Do we just decompose body and spirit at death?

Undoubtedly. Again, I have no problem with ‘yes’ to that one either.

What happens to our consciousness/spirit/soul when we die?

I already sense an answer to this one – this time by answering a converse question: ‘where was our consciousness/spirit/soul before we were born (or conceived, according to one's view of when life begins)?’ My view is that we have already experienced the ‘here-after’ in its alter ego, the ‘here-before’. Our recollection of it is zero, despite Shirley MacLaine’s claims. It seems logical that any conscious-ness/spirit/soul we had in the ‘before-life’ should revert to the same form in the ‘after-life’. Why should its past form be different than the future form? Materially, our individual lives, during the organizing and reorganizing matter from non-living to living and back again, are way stations in the matter of which we are made. Our bones will become the differently-organized mineral calcium phosphate, our protein will be re-shared with other life forms, and our blood salts will merge with sea salt. Body and soul are one.

My view of the living spirit/soul hinges on the notion that life goes inexorably onwards and upwards. Of the two choices, one granting ‘advantage’ and prolonged life (order), and the other, ‘disadvantage’ and curtailed life (early return to disorder), the path to ‘advantage’ bestows representational rights in following generations. ‘Choice’ seems to follow more closely the gift of self-locomotion. Plants, not having that gift, thrive where they may. They change within their lives only by adaptation, and in their progeny, by mutation. But motile organisms making good choices will survive, when similar ones making bad choices will not survive, hastening change. Self-propelled organisms share this ‘choosing’ ability, which I judge is the seat of consciousness.

The humblest motile organism I know of that exhibits ‘choice’ is a tiny oceanic organism. Perhaps many species do this, but one example is all we need to make the point. This organism ‘dances’ using minute flagellae around its body, and the dance varies according to the wavelength of the light in which it is bathed. The two kinds of dance are described as the ‘blue’ dance and the ‘red’ dance.

It is zoo-planktonic, and feeds on blue-green algae floating in the ocean, almost at the surface. Wind action drives the algae into ‘windrows’, long lines at the sea’s surface, to become plant-food for this small herbivore. The algae use part of the light shining on them to sustain growth, and the light below them is changed accordingly. When the flagellate creature is amid the algae it feeds on, it ‘sees’ the remaining color, which lacks blue/green components, appearing reddish, and performs a vertical oscillating dance. As long as it is feeding the dance places it at different vertical stations within the windrow.

When the same flagellate is out in the open between windrows, it ‘sees’ a different color with more blue in the light spectrum, because the algae is not there to absorb the blue/green light component. Then the organism dances laterally, side-to-side. Sooner or later the dance brings it to a new windrow, and the pattern reverts to vertical oscillation, maintaining its position to benefit from the ‘choice’ so made. If organisms follow no pattern, they suffer a feeding disadvantage. ‘Choice’ propelled the evolution of this organism towards more efficient versions of the original. I hope nobody out there reading this contends that evolution is ‘only a theory’.

I see ‘consciousness’ in more complex organisms (i.e., the higher animals), as an enormously multifaceted complex of many such ‘choices’, some more important than others. The more important ‘choices’ over-ride the less important. Some choices are conscious, some are embedded in the nervous system, but they still represent a ‘choice’—like when you instinctively withdraw the hand from a hot surface. Breathing is unconscious, but drinking is a conscious choice—we can have water or wine now—or we may choose to wait a little longer until the tea has brewed.

When the body dies, choices no longer have consequences, so there is no further need for the spirit/soul. I contend the soul is not eternal, and is not recycled. I utterly discount Shirley MacLaine’s claims to previous lives. Because she is famous and has money, most people forget that she made it by playing very convincing ‘let’s pretend’ at the highest professional levels.

3. Granted a historic Christ, what do you believe about him?

Various authorities inform us that there were numerous Christs, the biblical one and many pretenders, which included a few genuine, earnest emulators. My answers refer to the biblical one, scourged and crucified by the Romans, in the event instigated by local civic leaders in Jerusalem in Judaea.

He was the subject of many idealized life stories, of which just four were chosen for that great piece of literature, The Bible. These stories stretch credulity far beyond breaking. Walking on water? Turning water into wine? Rising from the dead? Who are we kidding? If the ‘wine’ miracle happened, were the usual laws of matter fleetingly revoked? Material laws yield to none, even temporarily. How did it happen? Perhaps Jesus read the character of a rascally steward who stashed away the good stuff for his own later use, and when confronted by Jesus, he was obliged to fetch it back out. Doubting Thomas? Never happened. Jesus was either dead and did not reappear to the apostles, or he was not dead and appeared as an injured self who recovered—certainly not resurrected after having been dead. Did anyone read Stephen King’s Pet Sematary?

However, from the several accounts of Christ’s life (all different, often in major details), one can tease out a core of the man’s reality. Undoubtedly he was a man with great charisma, deep love and concern for his fellow men, especially the downtrodden; sensitivity to social injustice; a compelling orator; well-versed in Mosaic law; and he held a deep-seated disdain for the pomp and hypocrisy of the ‘powers-that-be’—the Pharisees and scribes, the money-lenders, the rich men, the rulers, all filled with their own importance, and most of them on the take.

He was the object of their deadly conspiracy because his charisma and popular following threatened their social order, and their position in it—similar to the way many southern whites felt threatened by Martin Luther King, Jr. during the early days of my residence within these shores. Were a Jesus Christ born today, I believe he would hold precisely the same attitudes and values as the original Christ, with minor modifications to suit the present-day context.

I already described my view of the gospels—how the extant Greek and Roman god stories described many deities (and demons, too) with miraculous powers, among others, the ability to procreate with humans to produce demi-gods, and so on. The gospel makers wrote of Jesus’ goodness, love, forgiveness and tolerance as best they could, but I think they were tempted in the end to beef up his godliness by including miracles, so as to compare better with the other god literatures—curiously, the exact temptation that Christ was recorded as having resisted. So—no biblical-style miracles. I do believe in miracles, but of chance or the inner spirit. Common sense says miracles never overturn the laws of physics, chemistry and mathematics. . . . Having said that, comparing the Christian gospels with Roman and Greek god writings, I find the gospel stories commendably far more rational and sober, and the better for it—but they still overtax credulity.

There are two views, maybe more, of the resurrection. Either people saw another man with similar love and kindness towards his fellows, and metaphorically said ‘he is the Christ’, in the same the way people seeing me for the first time as an adult, say ‘goodness me, it is Stanley (my dad’s name) all over again!’ Or it is a wishful account of what should have been, were justice served—an attempt to reverse time, as if to deny Christ’s tragic last day—even after Christ showed a guilty adulteress a mercy, that he, an innocent, was denied. In that era women were stoned for adultery, and babies slaughtered on a seer’s prediction. That should not have been, but it was.

Was he God, man, or both?

From various readings on how the brain works, I gather that there is a basic human need for a ‘higher being’. This need has been met many times in many cultures, so that basically ‘man made God in his own image’—not the other way round. The god concept may be used for purposes noble or evil but is a human artifact. Most who follow a god do so for noble purposes, to gain inner strength and will, to better accept the adversities of life, and to help improve the lots of those less fortunate.

To me, with no god necessary for life to exist, and no evidence of a physically real god, the one Christ was undoubtedly a man, a very extraordinary man, but still—a man. In other writings I have suggested that there might be some benefit for believers if Jesus were seen as a man purely and simply. ‘Jesus as god’ offers no hope for the ordinary person to adopt Jesus’ loving and forgiving attitudes, and might cause one to complain ‘why bother? I am just a man, he was a god.’ But ‘Jesus as human’ permits a more optimistic attitude—‘If Jesus can, then I can too. Although I am sure he was not a god, I can accept reference to him as ‘god’ metaphorically.

This, by the way, is one reason why I attend a Lutheran church regularly. Although I am an atheist, I feel Christian in everything except the theological component. I regard the communion rite as a re-enactment of the poignant events and remarks surrounding Jesus’ last hours, at a time when he surely was aware of the nature and extent of the authorities’ conspiracy against him, and probably also realized the certainty that he would die because of it. If it takes a communion rite to remind people to behave with love and decency towards each other, I am happy with it, but I do not feel I need that reminder. While the rest of the congregation partakes of the ritual at the altar rail, I commune alone in the choir stalls, singing vocal soli of one or other of the lovely pieces written especially for communion—pure theatre on my part, but church members often say that it stirs them.

4. What do you see as the purpose(s) in our lives.

Does there have to be a purpose? I always question, and in the questioning mode a word I frequently use is ‘why’? Why do we need a purpose? What happens if we simply ‘get on with it’? In seeking answers I try to dis-associate by looking beyond the human species. It seems to help me focus objectively on the logic, by removing the subjectivity involved because of my status as a human. Thus I imagine, say, an anthill, and being uninvolved, I can answer in a more objective way ‘what do ants suppose is their purpose in life?’ The answer I keep reaching (outside the ecological ‘balance-of-nature’ concept) is: individual ants have no purpose, they just ARE.

In the material scheme of things our lives, our world, our solar system, our galaxy, and our universe, are all driven by thermodynamics. Objects exposed to energy, no matter the type or origin, respond by intercepting it or allowing it to pass. Intercepted energy begets change. The change is neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’ in character, since ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are purely human constructs, and wholly sub-jective.

Absorption of energy always causes low-energy substances to assume a higher energy. The change may be fleeting (briefly heated); or durable (they become other stable substances); or durable decomposition substances (the gaseous parts disperse, and the material is no more the same thing); the energy may be re-emitted soon afterwards with reversion to the original state; or long afterwards by another agency’s intervention; or remain ‘locked’ in the higher energy state, as in gases formed by decomposition. Thus sunlight changes carbon dioxide and water into green plants, glucose, cellulose, and oxygen, and a gamut of other materials in the process. Glucose and oxygen are high-energy substances, and of them we say that the plant producing them has stored the energy from the sun. We can release that energy metabolically to perform biological work, or we can release it chemically to do mechanical work—for instance, by burning the wood to drive a steam engine. While we still have much to learn about the details of our cosmos, nothing out there suggests we will ever have to change the basic laws governing energy and matter, although we may make modifications as new conditions impose boundaries for existing laws. For example, I see us discovering laws to apply under different conditions than at the earth’s surface, e.g., in the intense gravitational field near a ‘black hole’, but never actually overturning Newton’s laws of motion.

To me, life processes, geologic processes, cosmic processes, all are just thermo-dynamics at work. Our role in the universe is a small feature of the energy balance as it passes from source to receptor—each receptor being source to the next receptor in line, and so on. To me it all comes together as an elegant whole—nothing wasted, only changed. Furthermore, no matter how slow it seems on our time-scale, the changes are quite fast enough on the geological or cosmic scale.

5. The problem of evil in the world/tragedies caused by nature and man—how do you explain it?

Again I ask—‘do we need explanations?’ When I taught oceanography, I used a small book by Willard Bascom, Waves and Beaches, to describe wave motions and their effects. Bascom was an engineer, who went everywhere, did everything. He illustrated his chapter on tsunamis with a photograph of the harbor at Honolulu taken by a photographer from a safe vantage point several hundred feet above the impending danger, seconds before a several-hundred-foot wave crashed into the docking basin. This towering wave commanded the entire picture, but in the picture was one small corner of one wharf not yet inundated, but in a few seconds it would be. On the wharf was the lone figure of a longshoreman trapped by circumstance or carelessness, frantically trying to flee—to where?—there was nowhere for him to go—a ‘chance’ of location. In the same occupation in New York, Liverpool, or Marseilles, his life might have offered different, better, chances. The caption went something like—‘to the left center of the picture an unlucky longshoreman tries to escape the impending disaster’. His unfortunate end was a mere matter of chance. I suppose we could call this the quantum of tragedy—one man losing his life before his time in a vain fight against nature (in this case). It could just as well have been in a vain fight against the spiteful caprices of mankind in one of our many wars.

If we multiply this one death by a hundred, a thousand, a million, is it any more of a tragedy? I do not consider it so. The degree of tragedy for each individual death, in the eyes of those survivors closest to the deceased, is precisely the same in every case. The only difference in the cases lies in the number scale we use to measure things. The ending of life occurs to all of us, some sooner, some later. I think most people tend to agree that the defining feature of ‘tragedy’ is an untimely or needless death, snatched away from life into oblivion from the midst of a healthy, productive, joyous life. But is it more of a tragedy when 270 people are killed in one airline disaster rather than one driver dying in a car accident—or less, when 30,000 people annually die separate deaths in motor accidents? The scale may be different, but the individual intensity and experience is the same.

Humans are privileged to an extent found nowhere else in nature. Humans jealously count, and account for, each and every human life, documenting it from beginning to end—or we try to, anyway. But in the rest of nature, a different system operates. A typical small female bird lives ten years, and nests at least once a year after her first year. Here in the southeastern United States, many nest in both spring and fall. They typically lay up to eight eggs each mating season. If undisturbed, perhaps eighty percent will hatch. If the nestlings mature, in one year, they are capable of doing the same thing. One successful adult female bird could theoretically generate billions of offspring in her lifetime. But with mortality and predation being what they are, most adult females are lucky if, during a whole life, more than a few offspring survive. In the African veldt gnus are prey for lions, the Tommies (Thompson’s gazelles) are prey for almost all the lesser predators. When each one dies, life goes on. The animals culled by predation are most usually the sick, the old, or the young who cannot keep up, or those lacking sufficient experience to do what is needed to continue the competition. But through it all, although more young die than survive, many young do survive to maturity, promising continuity. I think the human penchant for documentation of every human life is what drives the supposition that a god would show the same concern for details of every life—from humans to the fallen sparrow, the lilies of the field, and so on.

In my opinion, individual survival is just a matter of chance, often helped by the actions of an aggressively watchful parent. Extending simple chance from the animal kingdom to the human realm, I see no reason to step outside the laws of chance (in some cases chance alone, in others chance coupled with poor life choices). One person comes down with a fatal disease and dies young, while a neighbor exposed to the same conditions does not. One with a heritable weakness of the lungs chooses to smoke, while his son chooses not to (my dad and I). One person traveling to the same office, over the same highway, for the same daily mileage as his peers, is killed in a car accident, while hundreds of his colleagues traveling the same roads live their entire lives with no such deadly mischance. Sad to see, when it happens, devastating for the immediate family, but mere chance nonetheless.

There is better authority than mine to say that god has no hand in survival, if chance is a sufficient explanation. According to philosopher-theologian William of Ock-ham, (Ockham’s Razor), the best explanation for an observed phenomenon is the simplest—meaning: do not impute complexity beyond the minimum that accounts for what you see. If, later, some new aspect of the phenomenon appears, one is not necessarily back at square one. A modification or addition to the original explan-ation, or defining boundary conditions, is often all that is needed.

Aside: Most creation theorists say that the theory of evolution is ‘only a theory’, and has been ‘disproved’ so many times it cannot be true. They ignore mountains of evidence supporting evolution, not the least of which is the accelerated selective evolution of food crops and farm animals within the short span of human history. The theory of evolution has not been ‘disproved’, just modified bit-by-bit to accommodate details unknown in Darwin’s time. Just as changing the value of ‘pi’ as we learn better how to find it more accurately does not disprove its value—so changes in Darwin’s theory do not deny the original, just add richness of detail. Its basis has never been changed or seriously challenged, yet creationists keep trying to replace it by a different theory that has no supporting evidence and cannot be tested. They threaten a return to the scientific stone age, as they try to claim authority that they want, but do not deserve.

Not one reputable scientist backs creationist theory over Darwin’s theory. How-ever, creation theorists are often able to buy opinions of even PhD biologists who will write papers to support any theory, if only it brings them grant money—a degrading outcome of the ‘publish or perish’ policy. The US public education system has become the laughing stock of the scientific world by putting creation theory (with its absence of valid supporting data), in science curricula, on the same footing as Darwin’s basic hypothesis (with its wealth of testable supporting evidence).

Back to the main drift: god is an unnecessarily complex explanation for what goes on around us whereas, in contrast, chance is simple, elegant, and sufficient. That, plus there already exists a mathematically sound basis for most observations about ‘chance’, that permit predictions, not of individual outcomes, but of overall outcomes—a sort of quantum theory of living objects.

Incidentally, Ockham was a major instrument in showing that the writings and sermons of Pope John XXII contained serious errors of logic, amounting to heresy. That pope was eventually dethroned, but the surrounding controversy led to Ock-ham’s excommunication—like he cared, when it was over. He devoted the rest of his life to deep aspects of logic. That Pope was the reason why it took so long for another to come along and adopt John XXIII as his papal moniker.

I regard as my philosophical progenitors, Kant, Hegel, Huxley (Julian, not Thomas, his father, nor Aldous, his brother), and Russell, to name a few. I have not read all of their works, just enough to recognize that we are all on the same map traveling the same roads. I was privileged to hear Julian Huxley and Bertrand Russell once a week for a long period of time when they ran the BBC panel program The Brains Trust with discussions of such topics as this, a seminal experience.

I feel most kinship with Bertrand Russell. You might say he was my intellectual progenitor, especially since he was alive, well and extremely intellectually produc-tive during my lifetime. I cannot consider myself his intellectual equal, although had I been born with a golden spoon in my mouth, who knows? After all, he was Viscount Russell of Amberley, the third Earl Russell of Kingston, with a brilliant mind to boot, and I was not most of those things, perhaps not any. However, he and I share a passion for mathematics, beautiful women, a heretical degree of skep-ticism, and a reliance on the evidence of the senses, extended as possible by tools to measure and detect things for which our given senses are inadequate, all coupled with logic used to the best of our ability.

MY ATTITUDE TOWARD THE BIBLE

I accept even the wildest biblical stories as allegory, metaphor, or cautionary tales devised for specific ends, but not as literal truths. I accept the notion of a god as an ideal devised by man. I do not accept a physical or tangible god of any kind. These two apparently conflicting ideas can be reconciled very easily (by me, at least) by noting that an ideal can inspire a person to perform some great feat, or to produce a great work of art, without the ideal itself having a concrete existence.

Most people (the intelligent ones!) understand that abstract concepts can have value in a concrete world—for example, mathematics is not real, but applications of its entirely abstract concepts probably do more than anything else to further our understanding of our surroundings and the way things work.

People not acquainted with thoughtful atheism (sometimes called ‘rationalism’—no capital ‘R’, which is something else), may be unaware that it does not deny the concept of a god, only the physical existence of a god. They might also note that atheists do not deny the value of Jesus Christ’s life and teaching; and that regarding the Bible as ‘literature’, rather than a wholly true account of real events, does not devalue it as a tribal history, a teaching tool, a compendium of moral tales, or a description of a way to approach life.

Regardless of what diet gurus try to tell us (one diet fits all), we are each an experiment of one. One person’s god-vision may be suitable only for that one person. Hence I consider it an ethical breach to promote ones own god-vision by telling another that theirs is wrong, and one’s own (or someone else’s), is right. Many people live wretchedly through no fault of their own, victims of circumstance far beyond their control; they sustain their life burden by almost any belief that offers them hope. To try to disprove such peoples’ beliefs, in my opinion, amounts to mental cruelty. However, if someone asks me about my own beliefs I am happy to explain, and that I consider is not an ethical breach. But in such discussions, and I have been in many, I try to make sure that if the person has a seriously different belief, that what life comes down to, in the end, is to make your way through it by any (decent) means possible, and if it requires a special belief system which works for them, so be it.

My final observation is that I know professed atheists who live decent lives, compassionate and caring for others, and professed Christians who do not even come close to those simple human ideals.